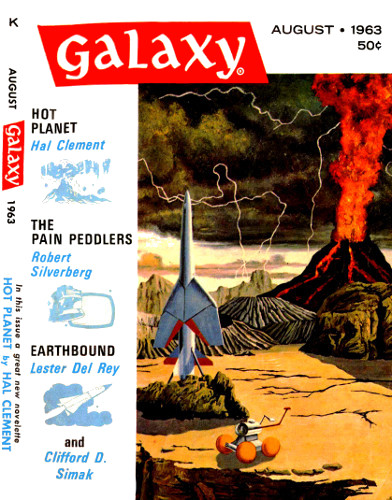

THE GREAT NEBRASKA SEA

By ALLAN DANZIG

Illustrated by WOOD

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Galaxy Magazine August 1963.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

It has happened a hundred times in the long history

of Earth—and, sooner or later, will happen again!

Everyone—all the geologists, at any rate—had known about the KiowaFault for years. That was before there was anything very interestingto know about it. The first survey of Colorado traced its course northand south in the narrow valley of Kiowa Creek about twenty miles eastof Denver; it extended south to the Arkansas River. And that was aboutall even the professionals were interested in knowing. There was neverso much as a landslide to bring the Fault to the attention of thegeneral public.

It was still a matter of academic interest when in the late '40sgeologists speculated on the relationship between the Kiowa Fault andthe Conchas Fault farther south, in New Mexico, and which followed thePecos as far south as Texas.

Nor was there much in the papers a few years later when it wassuggested that the Niobrara Fault (just inside and roughly parallel tothe eastern border of Wyoming) was a northerly extension of the Kiowa.By the mid sixties it was definitely established that the three Faultswere in fact a single line of fissure in the essential rock, stretchingalmost from the Canadian border well south of the New Mexico-Texas line.

It is not really surprising that it took so long to figure out theconnection. The population of the states affected was in places aslow as five people per square mile! The land was so dry it seemedimpossible that it could ever be used except for sheep-farming.

It strikes us today as ironic that from the late '50s there was graveconcern about the level of the water table throughout the entire area.

The even more ironic solution to the problem began in the summer of1973. It had been a particularly hot and dry August, and the ForestryService was keeping an anxious eye out for the fires it knew it couldexpect. Dense smoke was reported rising above a virtually uninhabitedarea along Black Squirrel Creek, and a plane was sent out for a report.

The report was—no fire at all. The rising cloud was not smoke, butdust. Thousands of cubic feet of dry earth rising lazily on the summerair. Rock slides, they guessed; certainly no fire. The Forestry Servicehad other worries at the moment, and filed the report.

But after a week had gone by, the town of Edison, a good twenty milesaway from the slides, was still complaining of the dust. Springs wasgoing dry, too, apparently from underground disturbances. Not even inthe Rockies could anyone remember a series of rock slides as bad asthis.

Newspapers in the mountain states gave it a few inches on the frontpage; anything is news in late August. And the geologists becameinterested. Seismologists were reporting unusual activity in the area,tremors too severe to be rock slides. Volcanic activity? Specifically,a dust volcano? Unusual, they knew, but right on the Kiowa Fault—couldbe.

Labor Day crowds read the scientific conjectures with late summerlassitude. Sunday supplements ran four-color artists' conceptions ofthe possible volcano. "Only Active Volcano in U. S.?" demanded theheadlines, and some papers even left off the question mark.

It may seem odd that the simplest explanation was practically notmentione